Guns from Afghanistan-

Helpful background information from OldGuns.net for prospective buyersWe get a lot of questions about guns being offered for sale in Afghanistan, and most of the ones we have seen appear to be recently made items. Frankly, since most are recently made copies and any that might be genuine antiques are in rather lousy condition, none are good investments as collector items. They do have value as a souvenir of time spent spreading freedom in a very different part of the world, so buy what you like.

The story below by noted arms authority William B. Edwards [whose "Civil War Guns" is still a standard reference in the field] appeared in the August, 1962, edition of GUNS magazine. Although it discusses the arms being made for the market 44 years ago, it should be obvious that these talented craftsmen can easily make virtually any type of muzzle loader with far less effort than required for a Webley revolver or Lee Enfield rifle. I expect that their production today is aimed almost exclusively at the American GI customers looking for "old guns" to take home. They are also quite adept at placing very official looking markings on any gun, including one Mosin Nagant rifle (probably a locally made one at that!) which was dated 1857 and passed off as an antique!

We salute all our troops serving in Afghanistan, and hope that this will help with their buying decisions.

Click here for a page loaded with tips on how to tell if a gun is old-- or newly made!

We would be glad to help ID any guns that you do find (preferably BEFORE you invest hard earned money in them) if you send up some photos. We have been helping the Bagram Airport customs people with this for quite a while, and are happy to help individual troops as well. We do not charge anything for this service, and you will normally get an answer within 24 hours.

Send us e-mail

The Gunsmiths of Darra

by William B. Edwards

GUNS Magazine, August 1962

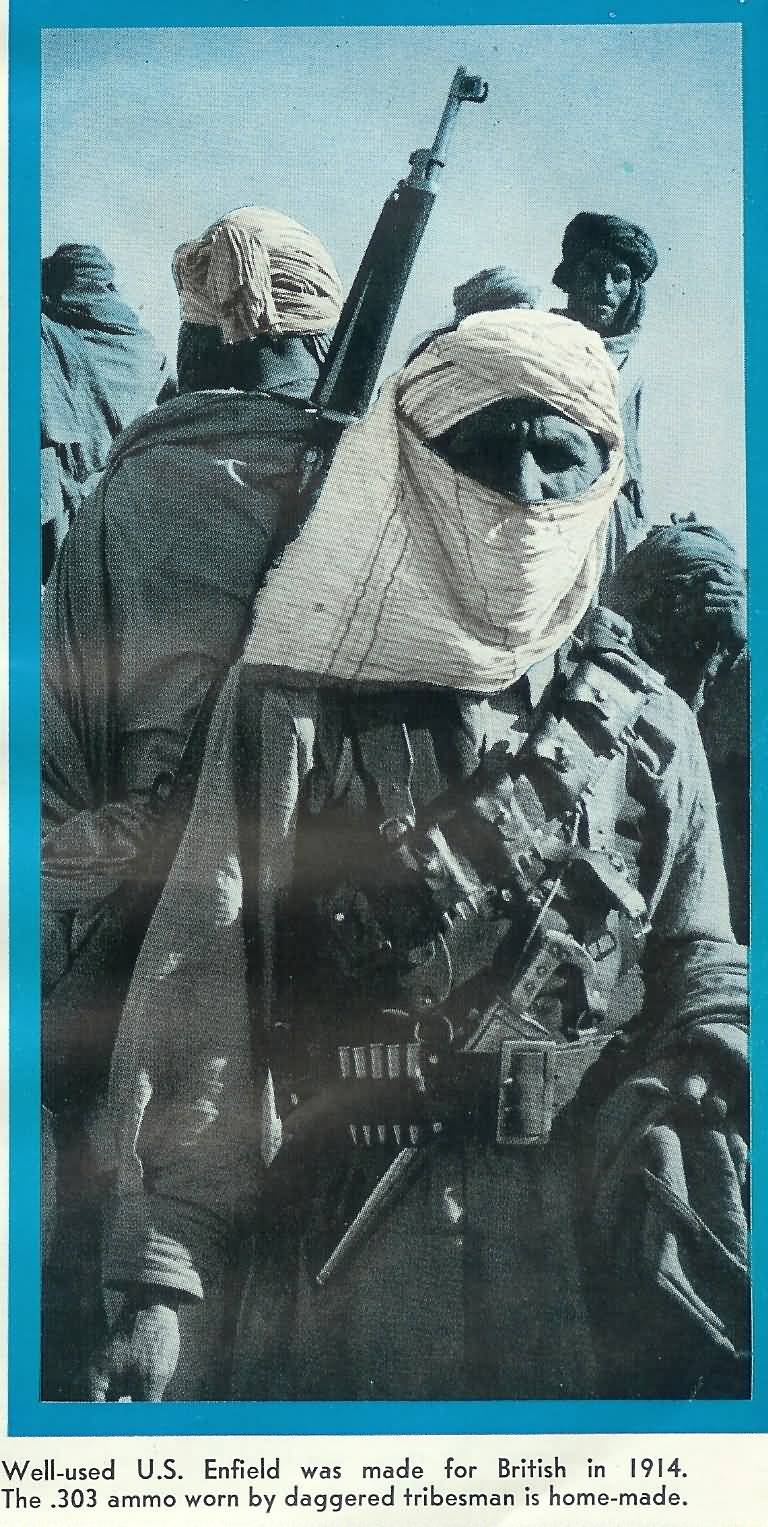

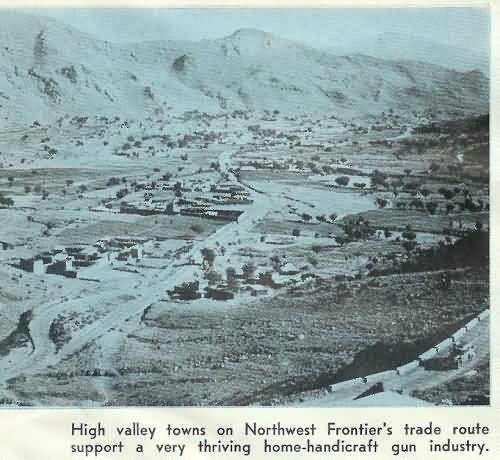

THIRTY MILES north of the last outpost of modern Afghanistan, on the road from Peshawar to Afghanistan, a sign warns, "Tribal Territory; Go Carefully." This marks the end of the authority of Pakistan President Field Marshall Mohammed Ayub Khan. From this point on, the land belongs to the proud and unconquered Afridi tribesmen-men not too much unlike our own American pioneers in their fierce independence and in their love for (and knowledge of) the guns they bear.

.

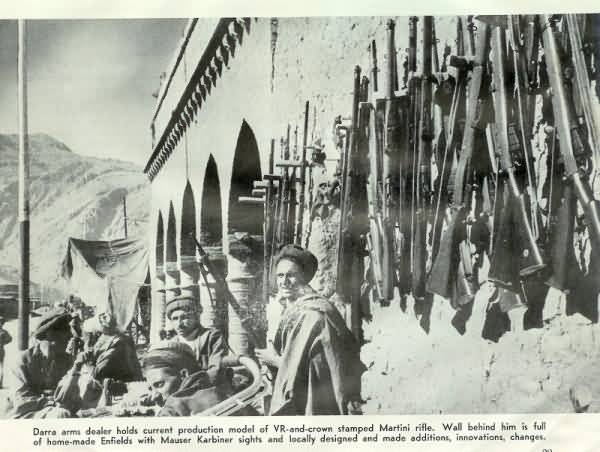

The main street of the town of Darra is the show place for a never ending gun collectors' convention. Since the days of battle-axes, these men have made weapons. Gunmaking skills date back to the long, curved stocked "jinghals" and the forward-striking matchlocks, festooned with ivory and brass, which were made here and shipped out over the trade routes of the East. Today, the Darra smiths are making modern guns, passable facsimiles of Webley revolvers in .38 and .45 calibers; wristbusting Martini-actioned pistols chambered for the powerful British .303 rifle cartridge; highly polished "Berettas:" and, naturally, rough but serviceable "Bren" machine pistols and burp guns. In a pile of captured rifles held by the Iranian army at Abas Abad Arsenal outside Tehran, I examined one of the Darra products: A "spittin' image" of a Czech VZ-24, with the carefully hand-stamped lettering "WAUSER-WERKE OBANDORF" on top of the receiver. For serial number, the Darra craftsmen had stamped a series of ampersands-&&&&&&; not very informative, but very official-appearing!

Darra is legally cut off by the governments of Pakistan and Afghanistan, but gun-running is old hat to the men of Darra; they get the guns out. It is said that you can have even a 40 mm Bofors cannon built in Darra, if you have the money and are in no particular hurry-and the betting is that the gun will be delivered (piecemeal, probably, but/ ready for assembly and service) almost wherever you want it.

Like everything else in Darra, gunmaking depends heavily on camels. Camels bring in the necessities of life, carry out the tools of death. In an earlier day, camels carried tribesmen on raids to steal rails from British railways. Chopped into convenient lengths, these rails were hacked and shaped and filed by Darra smiths into action bodies for Lee Enfield rifles. Today, camels bring raw iron and steel over the final stages of journeys from as far away as Belgium; but rails are still used too; where they come from is nobody's business. Files wear out, are at a premium, hence are used mainly for finishing. The rough work is by chisel and hammer, and I doubt that the word "gauge" can even be translated into the lingo of the hill tribesmen; yet they make parts that fit together into guns that shoot.

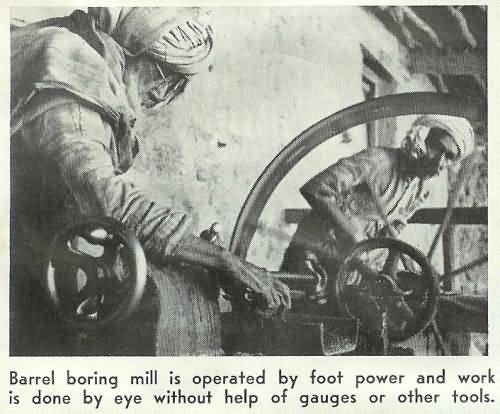

The boring of barrels is an art. Hand-forged on a common anvil to length and roughly to shape from the same friendly old Bessemer iron rails, the black rough barrel is then turned on a lathe to outside shape. These tools have no power except that of the knotty, muscled legs of the artisan ceaselessly working a treadle. With these tools, modern in the days of Alexander the Great, the Afridis produce firearms that, even on close inspection, have the well finished appearance of western work. (That they are butter-soft, and that the barrels are not necessarily bored down the middle, are considered minor objections.)

To get the hole inside the barrel, a horizontal boring rig is used taking one barrel at a time, of course. A string, attached to the mounting clamp for the bit, runs forward toward the muzzle, from whence a heavy stone weight pulls it into a hole in the ground. As the bit cuts into the barrel from the breech end, the stone drops into the pit, drawing the drill along. Boy-power on a flywheel handle furnishes the drilling motion and water the lubricant. This done, such matters as fine boring, reaming, and straightening are given minor attention, though at the last a surprisingly good finish is obtained. Shotgun barrels, bored from the solid this way, are lapped by hand.

Rifling is by guess and by Allah, to localize a phrase. The rifling bench would be familiar to only those Americans who have studied the books on Kentucky rifles and the tools by which they were made. The frame work of the machinery is two mule shoes, at the ends of which are fixed guide rods. The bend of the "U" is welded, at the front end, to a stake set in the ground; at the rear, a solid tree stump is the support. Crossing the gap between the ends of the Us are solid plates as guides. The rifling rod itself is a flat piece of iron bar twisted evenly to give a spiral of approximately one turn in 12-14 inches. At its near end is a cross handle which the young "Harry Pope" of the hill tribes pushes. There is no fixture to index the barrel regularly-all is by eye and chance. The cutter is a small chip of steel with three teeth, about a half-inch long and 1/10" wide, set in a rifling rod that runs in and out when the workman pushes and pulls the handle.

With nothing but their eyes to guide them, these people have created an amazing array of hardware. The primitive arms once forged there might make an endless list. I have seen two pocket Model 1849 Colt revolvers, rudely but serviceably done, winsomely stamped ADDDRESSS COL. SSAML NEW NEW AMERICA, (as near as I can recall) with some of the S's lying on the side, for a change. Found by a collector in Turkey, they came once upon a time across the Great Road of Cyrus on the laden back of some groaning, fussing Bactrian camel, from the market place in Darra to the bazaars of the Golden Horn. But the modern list of arms from Darra is most impressive. Fabricated there currently are:

Shotguns, Martini system, single shot. Though not so good as Messrs. Greener's redoubtable Birmingham-made "GP" gun, they look almost as fine from a slight distance. And should Greener's be so unwary as to allow a genuine proof tested GP gun to fall into the hands of these clever tribesmen, you may be sure that very soon the big GP trademark will be seen "bootlegged" in Karachi or Delhi, impeccably imitated on the side of a Darra-made imitation.

...

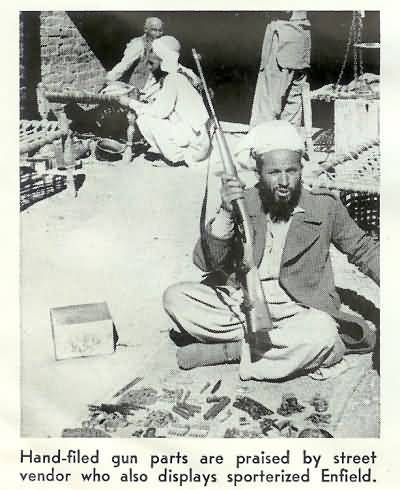

Rifles, Lee Enfield system. The Darra craftsmen roll with the times. Before World War II, Darra turned out the early models of Enfields. Though made of railroad iron, firing bullets salvaged from Army target butts and carefully filed clean of rifling grooves, these arms did constitute a war reserve potential which the Indian Government was unwilling to destroy. For years prior to 1941, the British administration in India had considered shutting up the Darra factories. As Brigadier C. Aubrey Dixon, subsequently Chief Inspector of Armaments of Pakistan, puts it, the closure "never came about because of many major political considerations." Certainly one major political reason was the strategic location of these independent tribesmen across the route of access to the Indus valley and the plains of India, from the North. India, historically fearful of invasion from the North, preferred to keep the mettlesome Afridis in business to give warning and a first defense line in case of invasion. Closing the tribal factories would not have been practical, anyway. The Afridis, if refused the right to labor in the craft they loved (and lived by) would merely return to pillaging and border raiding. Further, every cottage in the hills was engaged in one way or another in this gun trade, the families filing out parts, to scale if not to gauge, for later assembly in one of the village shops. If the trade was suppressed in one place, it would merely spring up again somewhere else.

But one practical suggestion was attempted: buying up the output for use by the Police. The quality of the Darra products was too poor to make the police very happy, but it was the right idea. In 1942, the tribesmen agreed to the removal of all their "machinery" to Peshawar, where six separate "factories" employing over 800 men were in operation by January, 1943. Tabbed "Police Arms Factories," these stable-boy craftsmen were producing 1200 rifles a month-about 1 1/2 rifles per workman per month. Not bad, for hand tools, hand (or foot) powered.

Rifles made in Peshawar were Lee Enfield No.4, and the Martini-Henry. The Martini was more popular with the Afridis, who recognize, as the mark of top quality in this rifle, the Imperial Crown over VR-made during the reign of Queen Victoria! Hence hill rifles stamped with these markings-but dated 1946 or later are still made!

A special Darra version of Mauser cum Enfield has been built in the hills. It has the receiver and two-piece stock of the Lee Enfield, but the barrel and front band, with bayonet stud, are finished like the short M1924 Mausers. Caliber is almost invariably .303, but 8 mm is also made. Whether .303 cartridges will work in Darra 8 mm rifles, and vice versa, is an experiment I have not cared to try.

Basic copies of the Mauser have been made, usually the 1924 type commercial guns. The Model 1914.303 "American Enfield" and the M1917 are also copied, and a few Springfields are for sale. The influence of the Mauser salesmen in the days prior to WW II when Germany was not supposed to be making rifles is still strong. Though a Springfield copy vendor was overheard proclaiming the virtues of his rifle by crying "The Americans won the war, didn't they?," his customer, who preferred the Mauser, was not convinced.

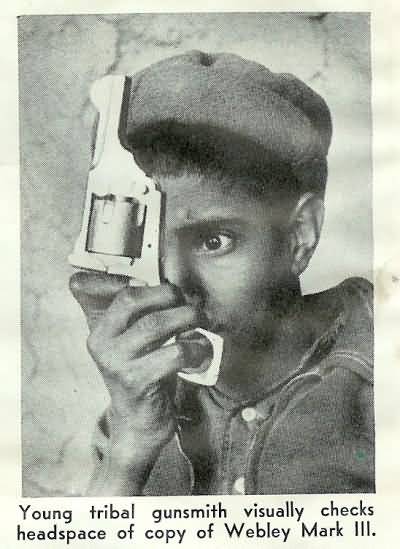

Handguns of Darra are so closely imitative as to fool the most discerning. Precise copies of the popular .38 Webley Mark III pocket and police revolvers are made with every Webley mark upon them in very neat simulation. The tops of the barrels used to be stamped "Made in U.S.A., Birmingham and London," but somebody finally explained where Webley is located, and now the words are simply, "Birmingham and London." The finish of these little pistols, with their recoil plates drawn to a bright straw color in simulation of Webley's finish, and their rich chemical blue, is surprisingly good; but there the quality ends. Others do, but I wouldn't shoot a Darra Webley on a bet.

Less neat are the .303 Martini pistols. Chambered for the .303 British Rifle cartridge, these sawed-off jobs are true pistols, built on the big military Martini rifle action. Inevitably, I suppose, some gun bug will get the yen to fire one of these, mainly to see if he can "take" it. I strongly advise, if you must do so, using a long, long string. The ammunition sold in the .Afridi shops is not SAAMI standard fodder; it is much weaker, put up in old British, Canadian, South African, Australian: and Indian-made cases, with bullets recovered from the butts and filed clean. Primers, as often as not, are actually reprimed - by knocking out the dents and filling with some mixture such as potassium chlorate or old match tips. The gunpowder may be any weight: say 32 to 38 grains, on the average. Chopped movie film is preferred! Velocities for this .303 are low, under 1300 f.p.s., and the main difficulty is getting the bullet out of the barrel. In a Martini pistol made for this junk, a good round might blow it up.

Since 1946, automatic arms have been appearing in increasing numbers in the hills. The tribesmen are reluctant to show anybody the shops where these guns are made.

Very good copies of the 9 mm M1938 Beretta "moschetto" are made, and the Sten gun is also copied. Fabricating the Sten is rather ridiculous, except for its durable qualities. The Sten was designed to be made cheaply by machinery, with a minimum of hand work. Chopping one out of rails and Belgian steel blanks is not easy.

It is reported that automatic pistols are now made north of Peshawar. Lugers are mentioned, but their existence is doubted. But if the Darra workers should manage to add the Luger to their list of wares, they would have achieved a real triumph. With movie-film ammunition and bullets undersized from shooting once before, to get any reliable functioning in a Luger would be a miracle.

Their tools are from the Early Iron Age, but the Darra gunsmiths have been hit by modern inflation. Ammunition prices between 1954 and 1959 have more than doubled, from about 9c a round to about 25c. Martini and Lee Enfield rifles that cost between $39 and $60 in 1954 have risen lately to $50 to $250. Webley revolvers at $18 (1954) have increased to $25, and automatic pistols are said to bring $100. The strict Communist regime in Tibet has caused some of the inflation: formerly, Chinese soldiers were willing to lose their rifles to the Tibetan chieftains for very little. Now, if a Communist Comrade peddles his one-time Lend Lease M1917, he may lose his head. With demand reflecting the supply, the Darra makers have hiked their prices accordingly.

Like arms makers the world over, the Darra tribesmen take no part in the great global conflicts which rage around them. They are content to work hard and make rifles, do a little shooting up of the countryside to let off high spirits, and then settle back to the serious business of gun trading.

Vice President Lyndon Johnson recently invited a Pakistani camel driver over to the U.S.A. to show him how things are done here. I'd like to invite Darra rifle factory owner Akbar Shah over to an American gun collectors' meeting. I think it would be quite an experience for both of us!